|

MESSAGE BOARD |

EMAIL ME |

HOMEPAGE |

INTRODUCTION |

TRACED |

LOST FRIENDS |

EVENTS |

GROUP PHOTOS |

ALBUM INDEX |

RINGWAY |

SERVICE RECORDS |

|

MESSAGE BOARD |

EMAIL ME |

HOMEPAGE |

INTRODUCTION |

TRACED |

LOST FRIENDS |

EVENTS |

GROUP PHOTOS |

ALBUM INDEX |

RINGWAY |

SERVICE RECORDS |

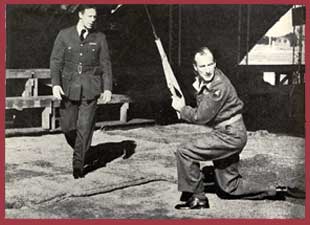

John Kilkenny instructs Maj Gen Bols |

|

The first training course at Ringway was in July 1941 with dummy drops over Ringway and Tatton Park. The existing Irvin 28ft parachute was used, from old but modified Whitley bombers and the first live drops were on 13th July 1941 when RAF instructors made eight test jumps. Two were pull-offs from a small open platform that had been fitted in place of the rear gun turret. The other six drops were from an aperture in the fuselage floor. The pull-off method required the parachutist to face into the aircraft's slipstream and then release the parachute which immediately tore him from the aircraft. The slipstream caused somersaulting and occasionally the feared 'candle' when the parachute failed to open properly. Pull-offs were soon abandoned, and it was decided to tie a secure line to the ripcord, which was fastened in the aircraft in the hope of achieving an automatic opening, with the canopy deploying first. |

Jumping through the `Whitley Hole' then became the norm, but even this method had serious disadvantages for

the hole was nearly three feet deep and unless a perfectly upright and rigid position was maintained the parachutist's

face would strike the inside of the hole - known as "ringing the bell"- with very painful consequences.

The first live drops of trainees were made at Tatton Park on 14July through the floor aperture of a converted

Whitley bomber. LAC Oakes was first, followed by six others, with just one injury. By 25 July, 135 drops had been

made when Driver R Evans RASC, of No.2 Commando, plummeted to the ground as his parachute failed to open

properly. This was the first fatality to be sustained but reserve parachutes were not issued to British airborne services

until 1955. |

There was an immediate halt to training and at this point Raymond Quilter of the GQ Company, was asked for his opinion. G stood for Gregory and Q for Quilter - two gentlemen, who since 1934 had been in business manufacturing parachutes. As it happened GQ had already produced a 28-ft parachute operated by static-line with the Army in mind, and within a week Quilter produced a new bag for the Irvin-type in which the rigging lines of the parachute were withdrawn from the bag before the canopy. The modification was thus a combination of the Irvin parachute with a GQ packing-bag and method of operation. The parachutist now hooked his static-line, which extended from inside the bag, to a strop attached to a bar running along the inside of the roof of the fuselage. The static-line then - together with the weight of the man - broke open the bag once the length of the line was fully extended after the man's exit from the aircraft and this enabled the rigging lines from the parachute to be withdrawn first and to be fully extended before the canopy filled with air. It had the added advantage of delaying the opening until the parachute was well clear of the aircraft. An upright body on exit was also more likely to ensure an unimpeded opening of the rigging lines and canopy. The effect of the aircraft's slipstream on the jumper was modified by the drag of the static-line and, if a good exit was achieved, the canopy was fully developed before much vertical height was lost. |

Leslie Irvin |

Tests with the new parachutes, aircraft fittings and other equipment were carried out and 500 tests with dummies were made before resuming live drops and by 8 August Strange and Benham were able to make the first landings at Tatton Park using the new Quilter 'statichutes'. A hectic period of adjustment followed , and from it finally emerged the GQ X – type statichute system. The parachute remained in service for the remainder of the Second World War and for a long time afterwards. It was the most effective static line parachute ever made, and its production brought together two rivals : Irvin to supply the air chute and GQ the statichute system. The parachute canopy measured 28 ft (8.5 m) in diameter and was made of silk, cotton (Ramex) and nylon - in that order - during the course of the war. |

Twenty-eight rigging lines converged below the periphery in four groups on `D' rings attached to lift webs. The rectangular inner bag when packed enclosed the folded canopy and a large flap was used to stow the rigging lines. This bag remained on the man's back after the rigging lines and canopy had been released. The outer pack resembled an envelope, the four flaps being lightly secured together by string in the front. The static-line was stowed in two pockets of the pack. Immediately after the parachutist's departure from the aircraft, the pack was left A seat strap formed by the main suspension straps passed in one continuous line from one set of rigging lines and up the other set of lines. Shoulder, back, chest and leg straps held the jumper in his seat strap. The man was locked in this position by a circular, metal box device. Four lift webs connected to the rigging lines formed part of the harness and some measure of flight control was achieved by reaching up and manipulating these webbing straps during the descent. |

|

|

In the early days at Ringway, parachutists - like the Germans - floated to earth steered by the prevailing air currents and made a forward roll on touching down. Flight Lieutenant Julian Gebolys, a senior Polish instructor, however, pioneered the art of arresting the speed, drift and oscillation of a parachute by manipulating the shoulder lift webs. Control was exercised over drifting in any direction and so the parachutist was prepared for forward, sideways and backward landings. After hitting the ground in the line of the drift, the principle of absorbing the shock was always the same. The force of impact was distributed between the combined strength of both legs and on one side of the body bv rolling on to the ground from the feet, through the thigh to the shoulder. |

During the early days, paratroopers carried no more on a jump than they could carry inside a small pack suspended across

the chest or inside the front body straps of the harness but John Rock experimented ceaselessly with suitable jumping apparel

and airborne supply equipment.

Finally , in 1941, the Denison' camouflaged smock was issued which meant that normal battle equipment could be worn under

the smock. Additional equipment was packed in a kitbag which was attached by rope to the paratrooper's lower right harness

strap, and secured also to the body by an ankle strap to the right leg. The 20ft(6m) length of rope was stowed in an exterior

pocket of the kit bag and paid out when the bag was released in flight by jerking out a pin on a corder attachment from the

ankle strap. A spring device absorbed the shock of the mid-air fall of the heavy bag. |

|

NEXT PAGE |